A Patent to Make Your Phone Less Useful

We've all been there. You are at a live event, and the person behind you can't seem to resist the urge to capture a shaky video or a grainy picture destined for the social media abyss. It annoys everyone around them, and it disturbs the performer. At the very least, people, turn off the flash.

Performers of all stripes have started to push back against the ubiquity of cell phone cameras. Some because they don't want material to leak online, others out of concern for the audience, and others because it distracts from the connection live performance can facilitate. Artists from Kate Bush to Adele have demanded fans stop recording their concerts. Benedict Cumberbatch has pleaded with them to watch Hamlet on the stage not on the 5 inch screen in front of their faces. Prince once filed a short-lived lawsuit against fans who linked to live recordings. Dave Chappelle and Alicia Keys are using locking pouches to help audience members overcome the temptation to pull out their phones. And Glenn Danzig will just put you in a headlock.

In response to this problem, Apple has patented infrared technology that, among other things, could disable recordings at concerts and other live events. Apple has announced no immediate plans to incorporate this "feature" in the iPhone. And despite the scourge of amateur concert videographers, we don't think it should. Dictating how we, as owners, use our devices, particularly when that involves disabling existing functionality at the request of a third party, erodes our property rights in the devices we buy.

Phone cameras, like any technology, can be used in socially helpful and harmful ways. But technology itself isn't very good at telling the difference between when we are behaving like good citizens and when we are being obnoxious. Your phone can't tell if Taylor Swift is disabling concert footage or the local police are preventing evidence of their abuse, for example. So to the extent we want some sort of regulation to discourage unauthorized filming, whether through law or social norms, we shouldn't bake those preferences into our devices.

Microsoft's War on Workouts

This is why I buy all my fitness videos on VHS.

Yesterday in a "sunset announcement," Microsoft informed consumers that purchases made through its Xbox Fitness service, which offers workout videos from the likes of Jillian Michaels and P90X, weren't exactly purchases after all. As part of the company's decision to scale back its support for the service, it offered users the following information:

So not only is Microsoft choosing not to produce or sell additional content—a choice it is, of course, free to make—it has decided that in a year, all the content its customers have "purchased" will disappear. This is just the latest in a long list of decisions that reflect a lack of respect for the property interests and reasonable expectations of customers.

Jane Fonda never would have pulled a stunt like this.

Good News for PS3 Owners, Sort of

You may not know it, but your gaming console is a powerful, compact, and inexpensive computer. With the right operating system and applications, it is capable of doing a lot more than running the newest first person shooter.

When it released the PS3, Sony used that fact to entice customers who thought it would be fun to install Linux on their consoles. Sony touted the "Install Other OS" function, which enabled console owners to do just that. But in March of 2010, Sony issued a firmware upgrade that disabled this functionality, and for many users stripped their device of much of its value. In an all too familiar story, a company's ability to force software "upgrades" proved a powerful tool for limiting the functionality of devices consumers thought they owned.

After years of litigation, the US District Court for the Northern District of California approved a class action settlement that compensates PS3 owners for Sony's overreach. While we think the court and the parties reached a reasonable resolution here, most of these sorts of abuses don't result in recovery by consumers. And even when they do, a check for a few dollars—six years after the fact—is a poor substitute for the right to use your property as you see fit.

Ebook Lending in Europe

Our writing has focused largely on the implications of the digital marketplace on individual consumers, but libraries face many of the same problems—and more. We've seen high-profile litigation between copyright interests and libraries over digitization, the HathiTrust case being the most recent example. But so far, we haven't seen libraries in the U.S. challenging restrictions on digital lending in court.

But the Vereniging Openbare Bibliotheken (VOB), a Dutch library association has brought suit to vindicate its “one copy, one user” policy for ebooks, which treats digital books much like their tangible counterparts. Advocate General Maciej Szpunar of the Court of Justice of the European Union recently issued an opinion endorsing the libraries' approach.

Crucially, the opinion begins with a recognition of the cultural importance of libraries:

Libraries are one of civilisation’s most ancient institutions, predating by several centuries the invention of paper and the emergence of books as we know them today. In the 15th century, they successfully adapted to, and benefited from, the invention of printing and it was to the libraries that the law of copyright, which emerged in the 18th century, had to adjust. Today we are witnessing a new, digital revolution, and one may wonder whether libraries will be able to survive this new shift in circumstances. Without wishing to overstate its importance, the present case undeniably offers the Court a real opportunity to help libraries not only to survive, but also to flourish.

He went on to find:

The lending of electronic books is the modern equivalent of the lending of printed books. I do not concur with the argument put forward in this case that there is a fundamental difference between electronic books and traditional books, or between the lending of electronic books and the lending of printed books....

[W]hat is in my opinion decisive is the objective element: in borrowing a book, either traditional or electronic, from a library a user wishes to acquaint himself with the content of that book, without keeping a copy of it at home. From that point of view there is no substantial difference between a printed book and an electronic book or between the methods by which they are lent.

While libraries can license ebooks from publishers, rather than relying on ownership, the Advocate General's opinion understood that there's a big difference between seeking permission and acting on the basis of a legal right to lend. Equally importantly, he recognized that market forces are not always sufficient to secure the benefits libraries have historically provided to the public:

Since time immemorial, libraries have lent books without having to seek authorisation. Some of them, legal deposit libraries, have not even had to purchase their own copies. That may be explained by the fact that books are not regarded as an ordinary commodity and that literary creation is not a simple economic activity. The importance of books for the preservation of, and access to culture and scientific knowledge has always taken precedence over considerations of a purely economic nature.

Today, in the digital age, libraries must be able to continue to fulfil the task of cultural preservation and dissemination that they performed when books existed only in paper format. That, however, is not necessarily possible in an environment that is governed solely by the laws of the market. First, libraries, and public libraries especially, do not always have the financial means to procure electronic books, with lending rights, at the high prices demanded by publishers. That applies especially to libraries operating in disadvantaged areas, where their role is most important.

Silverman on Smart Blenders

In the New York Times Magazine, Jacob Silverman, author of the insightful Terms of Service: Social Media and the Cost of Constant Connection, writes about the proliferation of so-called smart devices, a trend that is now teetering on the edge of self-parody.

His take is spot on:

The intelligence given to these devices really serves twin purposes: information collection and control. Smart devices are constantly collecting information, tracking user habits, trying to anticipate and shape their owners’ behaviors and reporting back to the corporate mother ship. Data is our era’s most promising extractive resource, and tech companies have found that connecting more people and devices, collecting information on how they

interact with one another and then using that information to sell advertising can be enormously profitable....

But the true ingenuity of a “smart” device is the way it upends traditional models of ownership. We don’t really buy and own network- connected household goods; in essence, we rent and operate these devices on terms set by the company. Because they run on proprietary software, and because they are connected to the internet, their corporate creators can always reach across cyberspace and meddle with them.

Publishers: Ebooks Are Sold After All

Despite the prevalence of the "Buy Now" button, publishers, labels, studios, and retailers insist that the digital products they provide are "licensed not sold." There's a simple reason for that. If they don't sell it, you can't own it. And if you don't own it, they can control how, when, and where you use the products you buy. So the message sent to consumers, even if it isn't particularly clear, is consistent.

But it turns out, copyright holders aren't exactly sticklers for consistency on the license vs. sale question. As we discuss in the book, when it's in their best interest to characterize a transaction as a sale rather than a license, they are more than willing to do so—even if those are the very same transactions they tell consumers are absolutely-unquestionably-swear-to-god licenses. We've written about the efforts of record labels to weasel out of royalty payments due to recording artists by calling digital downloads sales rather than licenses. Labels, you see, owe artists relatively small royalty rates on each sale under their recording contracts, but owe much larger rates on licenses. Unsurprisingly, when artists want to get paid for those billions of iTunes downloads, the labels call them sales and pocket the difference. Artists like Eminem have successfully sued labels over this practice.

A new class action lawsuit filed against Simon & Schuster alleges that the publisher tried the same tactic with authors. It told consumers that ebooks were licensed, but paid authors as if they were sold, denying them half of their royalties as a result. We'll see if the court insists on a greater degree of consistency.

LA Times on The "Buy Now" Button

One persistent problem facing consumers in the digital marketplace is the blurred line separating sales, which have traditionally conferred some form of property interests, and other transactions, often dubbed licenses, which don't. As we discuss at length in the book, the challenges of navigating the marketplace are exacerbated when retailers use language like "Buy Now" to appeal to consumers' familiarity with traditional sales, but bury licensing restrictions in the fine print.

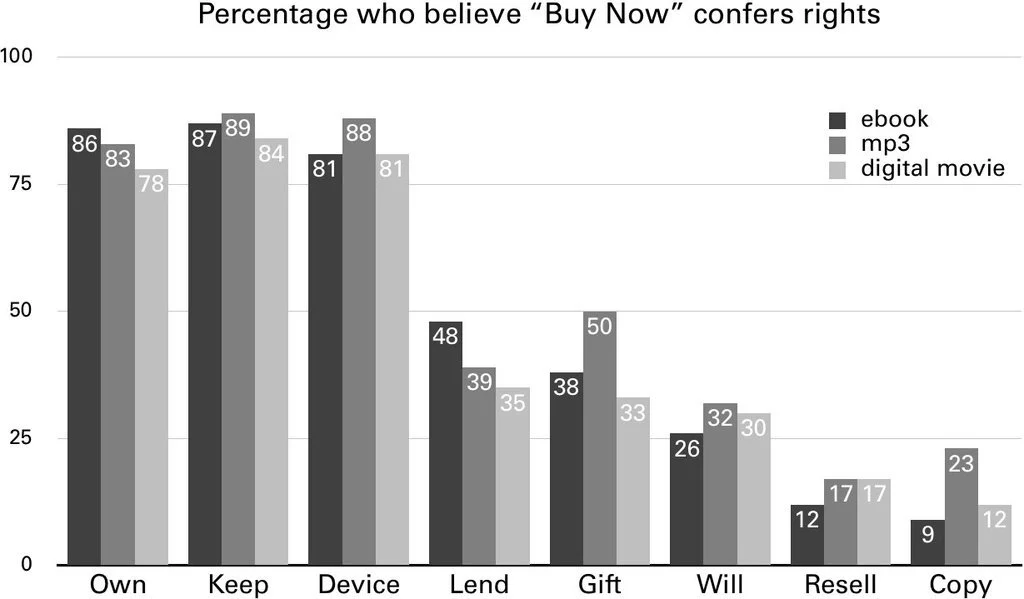

Today, the LA Times reported on the study I conducted with Chris Hoofnagle that shows a significant number of consumers believe that, when they "buy" digital goods like ebooks and mp3s, they acquire the rights to lend, give away, and otherwise transfer those purchases. The relevant license agreements, however, tell a different story.

Our study is set to appear in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review next year, but the findings are discussed in detail in The End of Ownership.

An Epilogue of Sorts

Days before we submitted the final draft of our manuscript to MIT Press, news broke of Nest's decision to kill the Revolv. A device that consumers bought and reasonably assumed they owned was rendered worthless by the very company that sold it to them. This was precisely the sort of abuse of law and code that motivated us to write this book. Luckily, we had time to include it.

But as we wrote The End of Ownership, we became increasingly aware of the seemingly limitless supply of developments that illustrate the worries we express about consumer property rights. And now that the book nears final production, it feels like those stories have only increased in their frequency. In just the last week, we've seen reports that Kobo users will lose hundreds of book titles thanks to a software "upgrade"; that iTunes users risk losing gigabytes of their personal music collections when they sign up for Apple Music; and that Apple plans to stop selling downloads altogether in favor of a purely subscription-based model. [Apple subsequently denied that report, for what it's worth.]

We always knew that the shifting relationship between consumers and the products they use was, by definition, a moving target. The history, themes, policies, and examples we cite in our book tell—we hope—a compelling story about the risks facing personal property in our increasingly digital economy and the steps we should take to preserve ownership. But we intend to supplement that story here, in part by adding to the long list of incidents that demonstrate the assault on consumer rights, but also through new analysis of the broader trends we observe.